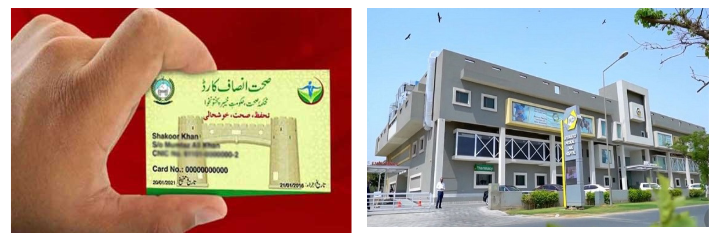

The Sehat Insaf Card was introduced in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in 2016 with the aim of ‘revolutionising’ the healthcare system across the province. The scheme was later expanded to other parts of the country, including Punjab, Balochistan, merged districts, Gilgit Baltistan, and Azad Jammu and Kashmir. However, after eight years, there remains uncertainty about whether investing in this health insurance scheme provided the optimal value for public funds.

The introduction of the Sehat Insaf Card by the PTI government in September 2016 wasn’t a novel concept. Before that, then-Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif had already implemented a state-run health insurance initiative known as the ‘PM’s National Health Programme’ on 31 December 2015, in line with the World Health Organisation’s (WHO’s) recommendations on universal health coverage. This programme aimed to provide quality healthcare services to the underprivileged, initially focusing on Islamabad, with plans for expansion to all provinces and the then-Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA). However, the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) and Sindh governments did not join the federal initiative, with KP introducing its own Sehat Sahulat programme in selected districts of the province.

However noble its objectives, the Sehat Insaf Card has been criticised for lavishing state money on the already rich, for neglecting government hospitals, and for allowing free rein to private hospitals to make money at the government’s expense.

The introduction of the Sehat Insaf Card by the PTI government in September 2016 wasn’t a novel concept. Before that, then-Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif had already implemented a state-run health insurance initiative known as the ‘PM’s National Health Programme’ in January of the same year.

In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

Launched on 1 September 2016, the Sehat Insaf Card initially covered 50 per cent of KP’s population for a two-year programme at the cost of Rs5362.2 million, providing free medical treatment facilities through designated private and public sector hospitals. By 2020, the Sehat Card Plus was initiated to cover the entire population of the province. However, independent experts question the effectiveness of this scheme in providing good healthcare sustainably.

Dr Mohammad Shahjehan, Emergency Registrar at the University of Lahore Teaching Hospital, Lahore, pointed out several flaws in this insurance scheme. In his opinion, Khan’s decision to launch the card just one-and-a-half-year before the elections in 2018 appeared to be motivated by electoral politics and was meant to appease the people in KP.

Dr Farid Midhet, Senior Professor of Community Health Sciences at Bahria University, Karachi, said that most of the projects launched by political governments have a political dimension. “Without a doubt, PTI gained popularity in KP due to the Sehat Insaf Card,” he said.

The rest of Pakistan

This programme was later replicated in Punjab in 2021, starting with seven districts. By 2022, the programme had been expanded to Islamabad, Balochistan, merged districts, Azad Jammu and Kashmir, and Gilgit Baltistan through the Federal Sehat Sahulat Programme.

Currently, 43,517,712 families are enrolled in this programme according to the Sehat Sahulat Programme website.

Private hospitals mint money

Dr Shahjehan said that treatment at private hospitals costs much more than receiving the same treatment at a government facility. The Sehat Sahulat scheme was launched without giving proper thought to sustainability. According to a Dawn report published in December 2021, more than 80 per cent of the hospitals registered under this programme, belong to the private sector, making them the main beneficiaries.

In Punjab, Sehat Sahulat Card was launched at a cost of Rs440 billion initially for three years. Instead of upgrading infrastructure, equipment, and human resources at government hospitals to provide quality healthcare on a sustainable basis, the PTI government recklessly allowed private hospitals to mint money from this scheme without proper monitoring. “We received data which showed that 90 per cent of gynaecology cases treated under the Sehat Sahulat Programme were C-sections, suggesting potential misuse. Additionally, individuals were provided with stents without genuine medical necessity.”

Dr Midhet seconded Dr Shahjehan and said that private hospitals are exploitative because the government does not have a monitoring system like in other developed countries. “Our aim should be to strengthen our government health facilities so that the poorest of the poor also avail this facility,” he said.

Dr Midhet added that at the time of Pakistan’s founding, around 90 per cent of the people used to avail of government hospitals’ facilities. “We have an elaborate network of government hospitals and the government owns tertiary hospitals. Some tertiary hospitals like Indus Hospital in Karachi are being run on charity. When the system of the government hospitals weakened, we should have fixed the system instead of bringing in a parallel system. In the 1960s and 1970s people used to rely on government health facilities.”

Inequitable coverage

Dr Midhet said that the objective of a government-funded health insurance card is always to help the poor but, unfortunately, it did not happen in Pakistan. “Poor people can be divided into three categories: mildly poor, poor, and the poorest of the poor. In such cases, the poorest of the poor are unable to have access to these facilities, for which there are several reasons. For instance, they may not have computerised national identity cards (CNICs) required for registeration in the scheme, they may be unaware of the facility, and may also be exploited by other people. Only those who have some knowledge about the programme can avail the facility,” he said.

Dr Shahjehan agreed that the scheme did not provide equitable access to healthcare, “One of the biggest shortcomings of this project was that it was open to all. Individuals who owned a land cruiser were allocated the same Rs1 million for inpatient treatment as a person living below the poverty line.” This led to a waste of public funds on people who could afford excellent healthcare from their own pockets.

Government-run facilities use public funds most optimally, as they cater to a large number of people. The equation changes when it comes to private hospitals, whose primary motive is to make profits instead of serving the people

Skewed health budgets

A major chunk of the health budget went into this scheme, putting immense financial strain on the government and public health infrastructure. “It turned out to be a disaster as the government ran out of money to fund government hospitals because most of the money was going to the Sehat Sahulat Card,” Dr Shahjehan said.

As per Dr Shahjehan, Mayo Hospital Lahore operates on an annual budget of Rs9 billion, serving the medical needs of 65 per cent of the city’s population. However, the government was unable to allocate sufficient funds to support the hospital. Consequently, there was a shortage of funds to pay employees and procure medicines, as the majority of the health budget was directed towards the Sehat Sahulat Programme. Regrettably, a significant portion of these funds ended up in the coffers of private hospitals.

Misusing the scheme

Dr Shahjehan believes that government-run facilities use public funds most optimally, as they cater to a large number of people. The equation changes when it comes to private hospitals whose primary motive is to make profits instead of serving the people. In some cases, private hospitals misused the scheme to charge the health insurance company higher bills than the amount incurred. “We found that sometimes hospitals charged the insurance company for an expensive medicine while using a cheaper alternative under a different brand name.” In other instances, private hospitals used registered persons’ CNIC numbers to charge the insurance company for treatment that was never really required or offered.

For future

Punjab Chief Minister Maryam Nawaz has said that her government would review the scheme and remove its flaws to ensure the sustainability of this initiative. Dr Shahjehan said that the health project needs to be scrutinised and restructured, with proper checks and balances introduced. He proposed that the scheme should be divided into various categories, providing free-of-cost healthcare to the poor, while charging a percentage of the expenses from others, according to their financial status. “First and foremost we need to collect data for the people who live below the poverty line and provide them free of cost treatment,” he said.

He also advocated for bringing more government hospitals on the panel of the insurance company. “In this way, we will get money and we will be able to fund more public hospitals and medical institutions.”